What is a species and what is a race?

General comment on the concept of “class”:

From Aristotle to Linnaeus, species were considered to be fixed units. Fixed units are classes, just like the chemical elements that exist in nature as they were created. Classes also means "natural kinds". "Natural kinds" are defined by at least one essential characteristic. Every member of a "natural kind" must have this characteristic. A class member who loses this characteristic can no longer belong to this class. The chemical elements are an example of "natural kinds", for example platinum is defined by the number of protons 78. If platinum loses a proton, it is no longer platinum.

It has been known since Darwin that species evolve. So species cannot be classes, or "natural kinds". This would contradict the theory of evolution. This fundamentally differentiates the chemical elements from the biological species. An adult European Robin has a red throat. However, this trait is not essential because if a robin loses its red throat due to a mutation, then that mutated individual still belongs to the robin group.

"Natural kinds" are universal, i. H. they are (in our present universe) neither bound to a time nor to a space. Species and races, on the other hand, "exist" once at certain times in certain places. The American zoologist and philosopher Ghiselin concluded that species are "individuals"; because individuals are defined by the fact that they originated once and will once again become extinct. Since species are mutable individuals, the practicing taxonomist is faced with the problem of which of the mutable organisms he should actually cling to and classify. This dilemma is called "the species problem", which has not yet been solved.

Since species are not "natural kinds", the conclusion is often drawn that there are no species in nature at all, but that what we consider species are nothing more than our own conceptualizations, because we have the need to order and classify biodiversity. But that is the old philosophical problem of abstract group concepts that extends from Plato through the medieval universal dispute to the present day. What are the spiritual extracts that we draw from the abundance of things and processes from the real world to be observed? Numbers or equations are also not real things that exist in nature that one can see, hear or feel. Nevertheless, you need numbers and equations to be able to make progress and predictions in everyday life and in science, and nobody would say: “There are no equations”, as is often said in taxonomy: “There are no species”.

Existence means: the thing exists outside of our concept formation (“out there”); the opposite is "mental construct". But: arguments and predictions in science (= that which is goal-oriented and true in science) are not only based on actually existing things. Do numbers exist “out there”; is there a two-dimensional level “out there”? Mathematics doesn't work with realities either. Nevertheless, mathematics works with "discoveries", by no means with "inventions".

See p. 263/64 in Oeser et al. 1988:

“We understand the world in terms without these terms themselves being real. However: these terms correspond to the world in a way that enables our minds to accurately predict states of the world. But it is the nature of our mind. "

[Oeser, E .; Bonet, M. (1988): The Realism Problem. Wiener Studien zur Wissenschaftstheorie, Volume 2. Vienna: Edition S Verlag der Österreichische Staatsdruckerei].

Equations such as taxa are discovered in nature (often after many unsuccessful attempts) and only prove to be "suitable" when they can be used to make predictions about processes in nature. Equations like taxa are by no means arbitrary “inventions” of humans. The view that taxa are arbitrary confronts both the protection of species (the Red Lists) and the identification of species (what is it that is in the identification books?) with a not inconsiderable problem. What do we actually want to protect and what do we actually determine?

Species (and also races) have a certain form of "semi-reality", ie: the criteria of cohesion or separation are real, but group formation on the basis of these criteria is made by ourselves (Reydon, TAC; Kunz , W. (2019): Species as natural entities, instrumental units and ranked taxa: new perspectives on the grouping and ranking problems. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 126, pp. 623-636). A blackbird exists as an individual, but the taxon "blackbird" is only "semi-real". Nobody has ever seen the taxon "blackbird".

It is amazing that practicing taxonomy today largely ignores this problem. There is a significant criticism of this:

“Taxonomy as a discipline is often surprisingly ignorant of theoretical issues behind species definitions and the process of speciation”

(p. 122 in: Misof, B .; Klütsch, CFC; Niehuis, O .; Patt, A. (2005): Of phenotypes and genotypes: Two sides of one coin in taxonomy? In: Bonner Zoologische Beiträge 53, pp. 121-133).

And the American bio-philosopher David Hull (1935-2010) warned in 1970:

“We must resist at all costs the tendency to superimpose a false simplicity on the exterior of science to hide incompletely formulated theoretical foundations”

(cited in: Mishler, BD; Donoghue, MJ (1994): Species concepts: a case for pluralism. In : E. Sober (ed.): Conceptual issues in evolutionary biology. Cambridge / Mass .: Mass.Inst. of Technology, pp. 217-232).

What is a species?:

What one finds empirically is that the organisms are not evenly distributed in their properties. Biodiversity is not a continuum. The organisms are in groups. The organisms are held together or separated into groups by their properties (characteristics, relationship, etc.). These are species.

However, there are quite different factors according to which individuals in nature to be held together in groups. That is why there is no such unit as “THE SPECIES” in nature, but it all depends on which factors of group cohesion are considered. "Species" is not the same as "Species" (Reydon, TAC (2005): On the nature of the species problem and the four meanings of 'species'. In: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 36 (1), Pp. 135-158). Species can:

(1) connect individuals to one another via reproduction synchronously in time (reproductive communities), but they can also

(2) connect individuals diachronically along the course of time who, due to the origin of an evolutionarily significant characteristic, forming a separat phylogenetic branch (phylogenetic species), or species are

(3) diachronic kinship groups, connected by reproductive lineages and defined according to the degree of their kinship (genealogical species).

However, species can also be completely different groups (depending on the cohesion factor of the individuals).

Species are not ONE unit in nature, but are ontologically different units, depending on the point of view. The term “species” is a word used homonymously for different units. However, the various “species types” often largely overlap. In many cases this means that if two individuals belong to the same reproductive community, then they also belong to the same phylogenetic species. But it doesn't have to be that way: There are also cases where, for example, two groups are closely related to each other (i.e. to one and the same kinship group), but diverge widely in their phylogenetically significant characteristics and are therefore two different phylogenetic species.

Of course, the practicing taxonomy cannot live with multiple defined species. You then needed several identification books for each group of organisms (birds, butterflies, etc.). Therefore, in practice, taxonomy either works with only one type of species (e.g. Ernst Mayr only recognized the reproductive community, and modern taxonomy is mostly limited to the species concept of close kinship), or several factors affecting the cohesion of the organisms are integrated into an artificial unit, whereby it is decided subjectively which of the cohesive properties ultimately decides for the species delimitation. That is the "integrative species". Integrative species are artificial units close to nature..

The taxonomy thus lives with an incompatibility of the species as a theoretically consistent term and the species as an instrumental term for practical application. The American philosopher of biology David Hull says:

"The more theoretically significant a concept [of species] is, the more difficult it is to apply"

(Hull, DL (1997): The ideal species concept - and why we cant get it. In: MF Claridge, HA Dawah and MR Wilson (Ed.): Species: the units of biodiversity, Vol. 1. London: Chapman & Hall, pp. 357-380).

What is a race?:

The issue of race is put into a distorted light because of ideological and social needs. There is a risk that dominant ideologies and attitudes will endanger the freedom of science. Instead of explaining what a race is, it tries to deny the existence of races.

Zoology divides almost all species into races. In the case of birds alone, there are breeds in the higher six-digit number. Only species that have evolved completely new and endemic species that are restricted to a small geographical area do not have races. All species that are widespread worldwide can be subdivided into races.

The basic concepts of what a race is were established in the last century by the zoologist Rensch, the geneticist Dobzhansky and the taxonomist Mayr. Races are basically subdivisions of species. When a new breed is discovered, the species is always known already.

Races are "semi-independent" (i.e. incompletely dichotomous) evolving branches in the family tree, which are recognized and defined as branches due to the new development (apomorphies) of adaptive traits:

Kunz, W. (2021): Immer wieder missverstanden - Die Unterteilung von Arten in Rassen. In: Biologie in unserer Zeit 51 (2), S. 168–178.

Races usually differ from one another only in very few characteristics, which are adaptations to the local living conditions under which the races have developed. Races hardly differ in the general DNA sequences of their genomes. Racial differences are therefore not to be looked for in the DNA sequences that are neutral or that have nothing to do with local adaptations.

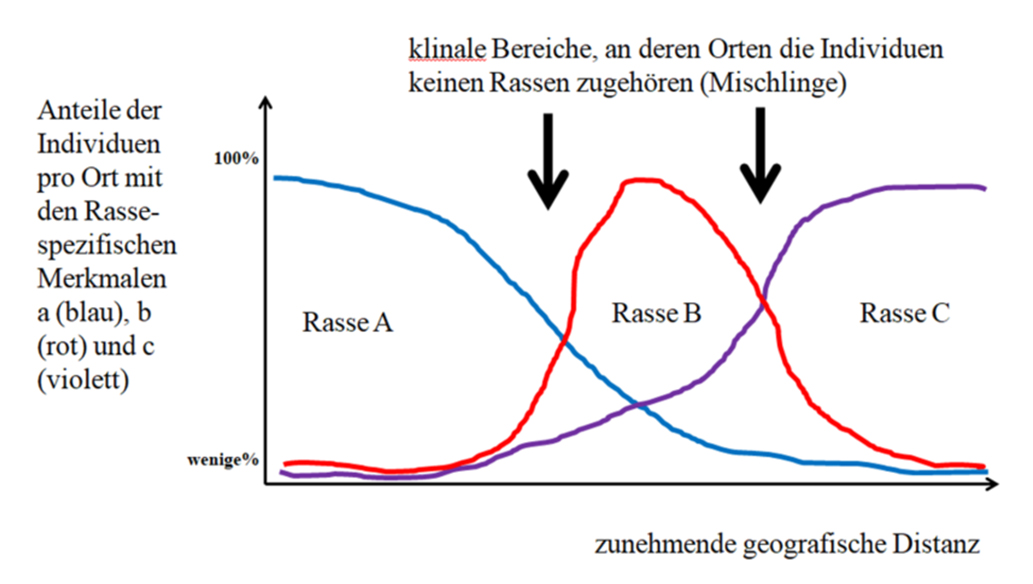

The reason why different traits develop in different races and also largely fix them is solely due to the geographical distance, which keeps sexual exchange between members of different races low. There are only very weak mating barriers. If the mating barriers get stronger, then this become species. The consequence of the lack of mating barriers is that in the zones in which different races collide, organisms live that cannot be assigned to any race (klinal transitions between the races).

It is a false assumption that races are an evenly geographically distributed continuous mixture of individuals with characteristic differences. In order to define races, characteristics (in)similarities are assessed between populations, not between individual organisms:

Mayr, E. (1963): Animal species and evolution. Cambridge, Mass .: Harvard University Press.